为配合G20宣传杭州丝绸文化。9月6日,央视纪录片频道、新闻网播出了对我校教授李加林的专访,以纪录片的形式介绍了李加林教授振兴丝绸行业的事迹。

原文如下:

国礼大师如何打开独树一“织”的密匙 | Face-to-face with a silk brocade master

Silk has been a cultural treasure for China for around 5,000 years. Not only is it revered by millions of Chinese, but it also remains highly sought after by the Western world, which has looked to import Chinese silk since the Han Dynasty (206 BC - 220 AD) through the ancient land and maritime silk routes.

Brocade, which sees silk woven into lavish colorful patterns, was reserved for the nobles in ancient times. Its unique and extremely complicated weaving process made it a status symbol for those who could afford this luxury.

However, modern times have seen traditional Chinese brocading techniques almost disappear from the fashion world. The craft of brocading can no longer satisfy increasing consumer demands for vibrant colors and soft texture.

For the thousands of Chinese brocade craftsmen working today, getting their craft back on the shelves and passing on their traditional and highly-skilled work techniques remain an enormous challenge.

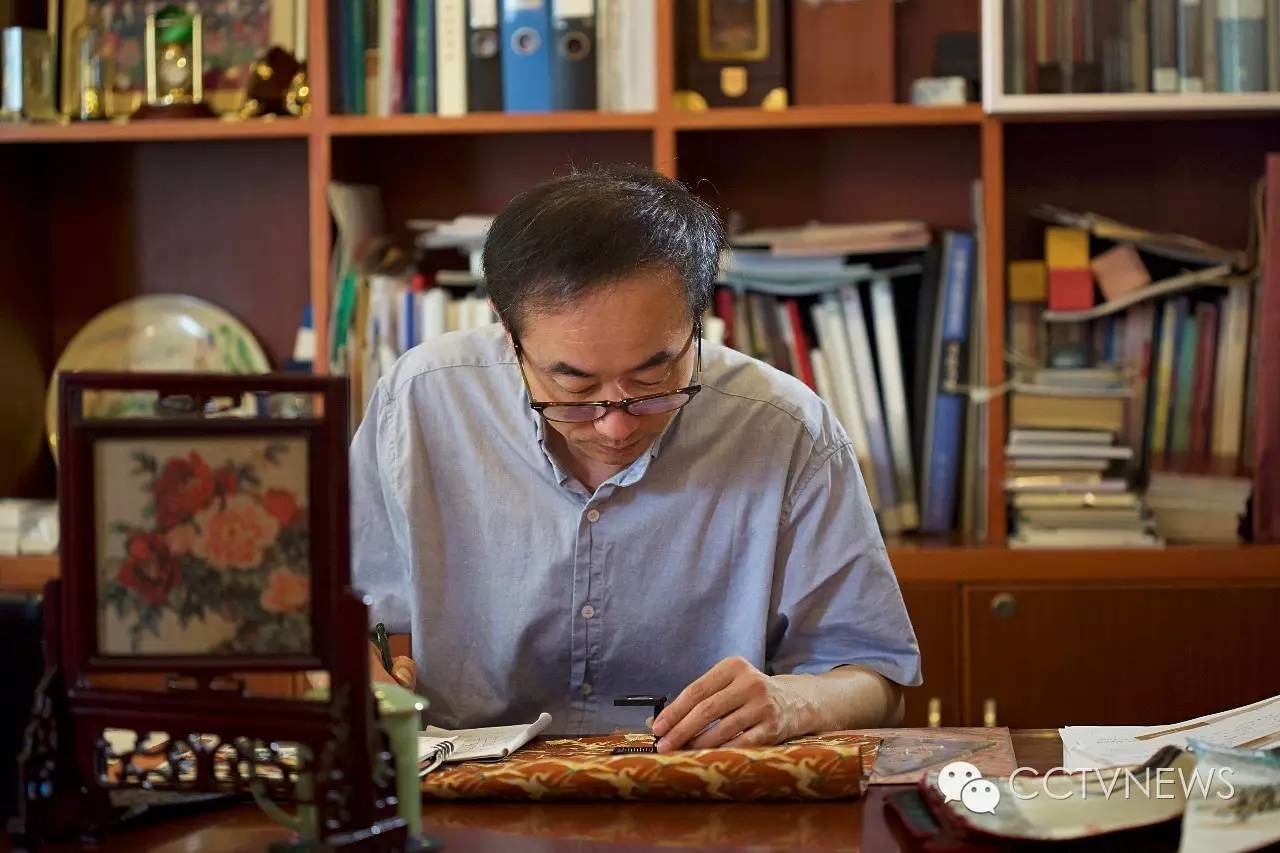

Li Jialin is one of several master brocade craftsmen who have spared no effort to promote the craft, and religiously try to steer it towards a more prosperous future.

According to him, Chinese culture has always been rooted in the silk industry, which means that modern embroidery still borrows heavily from the traditional silk craftsmanship.

Li has amazed the world with his intricate craftsmanship on works including a woven silk version of the Song painting Along the River during the Qingming Festival, as well as a brocaded copy of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War.

World’s first silk copy of The Art of War debut in 2005 and was presented by Hu Jintao as a gift to president George Bush in 2006.

Li shared his views on the renaissance of silk embroidery in an exclusive interview with CCTVNEWS.

As a key cultural product, silk, which has long been popular overseas, can on one hand help improve China’s cultural influence abroad, while on the other hand, provide an economic value as it competes with international fashion brands with its distinctive Chinese flair giving it a key advantage in the market.

Li spoke about how designs for brocade patterns on the qipao, a body-hugging traditional Chinese dress also known as a cheongsam, can draw inspiration from Chinese culture.

“We were once deeply impressed by the fascinating landscape of Hangzhou’s Jiuxi (a series of nine streams and 18 gorges in the city), where the stream slowly flowed into the distance and a bunch of butterflies danced in the air chasing the spinning peach blossom petals, so we contrived a special qipao with patterns to recreate the scene,” said Li, further indicating that traditional embroidery aims to represent a beautiful, romantic and typically Chinese scene.

While Chinese cultural elements should be applied to modern brocade, innovation in terms of design and technology to help push forward traditional embroidery is also of great importance to Li.

Li pointed out that Western fashion philosophy should be introduced into Chinese brocading techniques, so that the craft can cater to different fashion tastes. “Take the qipao as an example,” he said “besides the classical pattern of the ‘dragon and phoenix’ and ‘blooming flower and full moon’, we could add some chic designs or western fashion elements as well to make it richer in style.”

Innovation in design, however, can only be realized with modern technology.

Although Chinese brocading techniques were unparalleled during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, where even gold threads and peacock feathers could be used to make fabrics, the traditional craft on its own is unable to meet the modern world’s demands for a huge range of textiles and fashion goods.

Li Jialin has worked strenuously over the past 20 years to bring brocading into the 21st century, and his invention of the award-winning Digital Emulative Color Silk Weaving Technique has proved to be a big step forward.

Employing computer technology in both the design and manufacturing process has enabled silk weaving to produce an even greater variety of patterns, from landscape paintings to works based on photography, using some 4,500 colors. This development has also seen a huge improvement in the density of brocading fabric, making it even softer.

Li’s use of modern technology has also allowed craftsmen to customize the entire process to suit their needs, all the way from weaving the silk to tailoring patterns based on individual demand.

“While our customization started from a piece of cloth in the past, it now starts from a thread,” noted the master craftsman.

Through preserving Chinese cultural elements and constantly seeking new breakthroughs in both design and technology, “China should establish its own high-end brands for silk products to earn a position in the fashion world amid fierce competition with other international trademarks,” said Li, talking about his expectations for the future of the country’s silk industry.

“China has no lack of low and medium-grade goods as the world factory,” added Li, “but what we should strive to do is to create our own ‘Louis Vuitton’ or ‘Hermes’.”

With the 21st century “Belt and Road Initiative” now in motion, this precious material –whose prevalence along the ancient trade routes between east and west conferred the name the “Silk Road” – is now more than just a commodity.

Silk is an envoy, with the historic mission of promoting Chinese culture and bringing east and west closer. “While China’s economy has grown quickly, its culture should also be boosted,” Li said.

As one of the best representatives of the Chinese culture, “Chinese brocaded silk in modern times must reach out to the world.”

新闻来源网址: